Christabel Pankhurst on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Dame Christabel Harriette Pankhurst, (; 22 September 1880 – 13 February 1958) was a British

In 1905 Christabel Pankhurst interrupted a

In 1905 Christabel Pankhurst interrupted a  After obtaining her law degree in 1906, Christabel moved to the London headquarters of the WSPU, where she was appointed its organising secretary. Nicknamed "Queen of the Mob", she was jailed again in 1907 in

After obtaining her law degree in 1906, Christabel moved to the London headquarters of the WSPU, where she was appointed its organising secretary. Nicknamed "Queen of the Mob", she was jailed again in 1907 in

Britannica.com, Retrieved 21 September 2016 At the onset of World War II she again left for the United States, to live in

A profile bust of Christabel Pankhurst on the right pylon of the

A profile bust of Christabel Pankhurst on the right pylon of the

(Brewin Books, 2018 . Contains a chapter and analysis on Christabel Pankhurst's campaign in Smethwick, 1918.

1908 audio recording of Christabel Pankhurst speaking

* http://www.spartacus-educational.com/WpankhurstC.htm

Blue Plaque for Suffragette Leaders Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Pankhurst, Christabel British feminists English feminists English suffragettes English women writers Feminism and history Alumni of the University of Manchester Dames Commander of the Order of the British Empire People from Los Angeles People from Old Trafford 1880 births 1958 deaths People educated at Manchester High School for Girls Burials at Woodlawn Memorial Cemetery, Santa Monica Christabel Eagle House suffragettes Women's Social and Political Union

suffragette

A suffragette was a member of an activist women's organisation in the early 20th century who, under the banner "Votes for Women", fought for the right to vote in public elections in the United Kingdom. The term refers in particular to members ...

born in Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The t ...

, England. A co-founder of the Women's Social and Political Union

The Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) was a women-only political movement and leading militant organisation campaigning for women's suffrage in the United Kingdom from 1903 to 1918. Known from 1906 as the suffragettes, its membership and ...

(WSPU), she directed its militant actions from exile in France from 1912 to 1913. In 1914, she supported the war against Germany. After the war, she moved to the United States, where she worked as an evangelist for the Second Adventist movement.

Early life

Christabel Pankhurst was the daughter of women's suffrage movement leaderEmmeline Pankhurst

Emmeline Pankhurst ('' née'' Goulden; 15 July 1858 – 14 June 1928) was an English political activist who organised the UK suffragette movement and helped women win the right to vote. In 1999, ''Time'' named her as one of the 100 Most Impo ...

and radical socialist Richard Pankhurst

Richard Marsden Pankhurst (1834 – 5 July 1898) was an English barrister and socialist who was a strong supporter of women's rights.

Early life

Richard Pankhurst was the son of Henry Francis Pankhurst (1806–1873) and Margaret Marsden (180 ...

and sister to Sylvia and Adela Pankhurst

Adela Constantia Mary Walsh ( Pankhurst; 19 June 1885 – 23 May 1961) was a British born suffragette who worked as a political organiser for the WSPU in Scotland. In 1914 she moved to Australia where she continued her activism and was co-found ...

. Her father was a barrister

A barrister is a type of lawyer in common law jurisdictions. Barristers mostly specialise in courtroom advocacy and litigation. Their tasks include taking cases in superior courts and tribunals, drafting legal pleadings, researching law and ...

and her mother owned a small shop. Christabel assisted her mother, who worked as the Registrar of Births and Deaths in Manchester. Despite financial struggles, her family had always been encouraged by their firm belief in their devotion to causes rather than comforts.

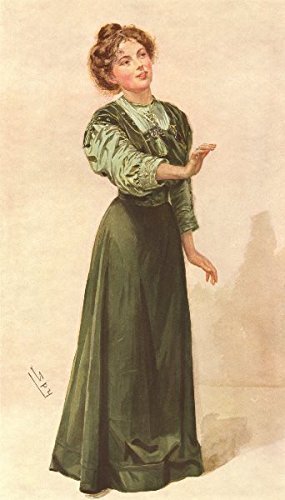

Nancy Ellen Rupprecht wrote, "She was almost a textbook illustration of the first child born to a middle-class family. In childhood as well as adulthood, she was beautiful, intelligent, graceful, confident, charming, and charismatic." Christabel enjoyed a special relationship with both her mother and father, who had named her after "Christabel", the poem by Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Samuel Taylor Coleridge (; 21 October 177225 July 1834) was an English poet, literary critic, philosopher, and theologian who, with his friend William Wordsworth, was a founder of the Romantic Movement in England and a member of the Lake Poe ...

("The lovely lady Christabel / Whom her father loves so well"). Her mother's death in 1928 had a devastating impact on Christabel.

Education

Pankhurst learned to read at her home on her own before she went to school. She and her two sisters attendedManchester High School for Girls

Manchester High School for Girls is an English independent day school for girls and a member of the Girls School Association. It is situated in Fallowfield, Manchester.

The head mistress is Helen Jeys who took up the position in September 2020 ...

. She obtained a law degree from the University of Manchester

, mottoeng = Knowledge, Wisdom, Humanity

, established = 2004 – University of Manchester Predecessor institutions: 1956 – UMIST (as university college; university 1994) 1904 – Victoria University of Manchester 1880 – Victoria Univer ...

, and received honours on her LL.B.

Bachelor of Laws ( la, Legum Baccalaureus; LL.B.) is an undergraduate law degree in the United Kingdom and most common law jurisdictions. Bachelor of Laws is also the name of the law degree awarded by universities in the People's Republic of Chi ...

exam but, as a woman, was not allowed to practise law. Later Pankhurst moved to Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaki ...

to live with a family friend, but, when her father died in 1898, returned home to help her mother raise the rest of the children.

Activism

Suffrage

In 1905 Christabel Pankhurst interrupted a

In 1905 Christabel Pankhurst interrupted a Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

meeting by shouting demands for voting rights for women. She was arrested and, along with fellow suffragette Annie Kenney

Ann "Annie" Kenney (13 September 1879 – 9 July 1953) was an English working-class suffragette and socialist feminist who became a leading figure in the Women's Social and Political Union. She co-founded its first branch in London with Minnie ...

, went to prison rather than pay a fine as punishment for their outburst. Their case gained much media interest and the ranks of the WSPU swelled following their trial. Emmeline Pankhurst began to take more militant

The English word ''militant'' is both an adjective and a noun, and it is generally used to mean vigorously active, combative and/or aggressive, especially in support of a cause, as in "militant reformers". It comes from the 15th century Latin " ...

action for the women's suffrage cause after her daughter's arrest and was herself imprisoned on many occasions for her principles.

After obtaining her law degree in 1906, Christabel moved to the London headquarters of the WSPU, where she was appointed its organising secretary. Nicknamed "Queen of the Mob", she was jailed again in 1907 in

After obtaining her law degree in 1906, Christabel moved to the London headquarters of the WSPU, where she was appointed its organising secretary. Nicknamed "Queen of the Mob", she was jailed again in 1907 in Parliament Square

Parliament Square is a square at the northwest end of the Palace of Westminster in the City of Westminster in central London. Laid out in the 19th century, it features a large open green area in the centre with trees to its west, and it contai ...

and in 1909 after the "Rush Trial" at Bow Street Magistrates' Court

Bow Street Magistrates' Court became one of the most famous magistrates' court in England. Over its 266-year existence it occupied various buildings on Bow Street in Central London, immediately north-east of Covent Garden. It closed in 2006 and ...

. Between 1913 and 1914 she lived in Paris to escape imprisonment under the terms of the Prisoner's (Temporary Discharge for Ill-Health) Act, better known as the "Cat and Mouse Act" but continued to provided editorial lead to ''The Suffragette'' through visitors such as Annie Kenney

Ann "Annie" Kenney (13 September 1879 – 9 July 1953) was an English working-class suffragette and socialist feminist who became a leading figure in the Women's Social and Political Union. She co-founded its first branch in London with Minnie ...

and Ida Wylie who crossed the Channel for her advice. Other campaigners visited Paris to have Christmas dinner with her in 1912; these included Irene Dallas

Irene Margaret Dallas (1883–1971) was a suffragette activist, speaker and organiser who held leadership roles in the WSPU; she was arrested and imprisoned with a group who tried to gain access to 10 Downing Street.

Life and activism

Irene ...

, Hilda Dallas

Hilda Mary Dallas (1878–1958) was a British artist and a suffragette who designed suffrage posters and cards and took a leadership role for the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). A pacifist, she raised funds from a cross-section of so ...

, Blanche Edwards and Alice Morgan Wright

Alice Morgan Wright (October 10, 1881 – April 8, 1975) was an American sculptor, suffragist, and animal welfare activist. She was one of the first American artists to embrace Cubism and Futurism.

Early life and education

Wright came from an ...

.

The start of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. The main belligerents included much of Europe and their colonial empires, the Russian Empire, the United States, ...

compelled her to return to England in 1914, where she was again arrested. Pankhurst engaged in a hunger strike

A hunger strike is a method of non-violent resistance in which participants fast as an act of political protest, or to provoke a feeling of guilt in others, usually with the objective to achieve a specific goal, such as a policy change. Most ...

, ultimately serving only 30 days of a three-year sentence.

She was influential in the WSPU's "anti-male" phase after the failure of the Conciliation Bills

Conciliation bills were proposed legislation which would extend the right of women to vote in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland to just over a million wealthy, property-owning women. After the January 1910 election, an all-party Con ...

. She wrote a book called ''The Great Scourge and How to End It'' on the subject of sexually transmitted disease

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs), also referred to as sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and the older term venereal diseases, are infections that are spread by sexual activity, especially vaginal intercourse, anal sex, and oral ...

s and how sexual equality (votes for women) would help the fight against these diseases.

She and her sister Sylvia did not get along. Sylvia was against turning the WSPU towards solely upper- and middle-class women and using militant tactics, while Christabel thought it was essential. Christabel felt that suffrage was a cause that should not be tied to any causes trying to help working-class women with their other issues. She felt that it would only drag the suffrage movement down and that all of the other issues could be solved once women had the right to vote.

Wartime activities

On 8 September 1914, Pankhurst re-appeared at London'sRoyal Opera House

The Royal Opera House (ROH) is an opera house and major performing arts venue in Covent Garden, central London. The large building is often referred to as simply Covent Garden, after a previous use of the site. It is the home of The Royal Op ...

after her long exile, to utter a declaration on "The German Peril", a campaign led by the former General Secretary of the WSPU, Norah Dacre Fox

Norah Elam, also known as Norah Dacre Fox (née Norah Doherty, 1878–1961), was a militant suffragette, anti-vivisectionist, feminist and fascist in the United Kingdom. Born at 13 Waltham Terrace in Dublin to John Doherty, a partner in a pape ...

in conjunction with the British Empire Union

The British Empire Union (BEU) was created in the United Kingdom during the First World War, in 1916, after changing its name from the Anti-German Union, which had been founded in April 1915. From December 1922 to summer 1952, it published a regula ...

and the National Party. Along with Norah Dacre Fox (later known as Norah Elam

Norah Elam, also known as Norah Dacre Fox (née Norah Doherty, 1878–1961), was a militant suffragette, anti-vivisectionist, feminist and fascist in the United Kingdom. Born at 13 Waltham Terrace in Dublin to John Doherty, a partner in a paper ...

), Pankhurst toured the country making recruiting speeches. Her sister Sylvia's memoir included a reference to some of Christabel's supporters handing the white feather

The white feather is a widely recognised propaganda symbol. It has, among other things, represented cowardice or conscientious pacifism; as in A. E. W. Mason's 1902 book, ''The Four Feathers''. In Britain during the First World War it was ofte ...

to every young man they encountered wearing civilian dress.

''The Suffragette'' appeared again on 16 April 1915 as a war paper and on 15 October changed its name to ''Britannia.'' In its pages, week by week, Pankhurst called for the military conscription of men and the industrial conscription of women into national service

National service is the system of voluntary government service, usually military service. Conscription is mandatory national service. The term ''national service'' comes from the United Kingdom's National Service (Armed Forces) Act 1939.

The l ...

. She called also for the internment of all people of enemy nationality, men and women, young and old, found on these shores. Her supporters bobbed up at Hyde Park

Hyde Park may refer to:

Places

England

* Hyde Park, London, a Royal Park in Central London

* Hyde Park, Leeds, an inner-city area of north-west Leeds

* Hyde Park, Sheffield, district of Sheffield

* Hyde Park, in Hyde, Greater Manchester

Austra ...

meetings with placards: "Intern Them All". She also championed a more complete and thorough enforcement of the blockade of enemy and neutral nations, arguing that this must be "a war of attrition

The War of Attrition ( ar, حرب الاستنزاف, Ḥarb al-Istinzāf; he, מלחמת ההתשה, Milhemet haHatashah) involved fighting between Israel and Egypt, Jordan, the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) and their allies from ...

". She demanded the resignation of Sir Edward Grey

Edward Grey, 1st Viscount Grey of Fallodon, (25 April 1862 – 7 September 1933), better known as Sir Edward Grey, was a British Liberal statesman and the main force behind British foreign policy in the era of the First World War.

An adhe ...

, Lord Robert Cecil

Edgar Algernon Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 1st Viscount Cecil of Chelwood, (14 September 1864 – 24 November 1958), known as Lord Robert Cecil from 1868 to 1923,As the younger son of a Marquess, Cecil held the courtesy title of "Lord". However, he ...

, General Sir William Robertson and Sir Eyre Crowe

Sir Eyre Alexander Barby Wichart Crowe (30 July 1864 – 28 April 1925) was a British diplomat, an expert on Germany in the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. He is best known for his vehement warning, in 1907, that Germany's expansionism was mot ...

, whom she considered too mild and dilatory in method. ''Britannia'' was many times raided by the police and experienced greater difficulty in appearing than had befallen ''The Suffragette.'' Indeed, although occasionally Norah Dacre Fox's father, John Doherty, who owned a printing firm, was drafted in to print campaign posters, ''Britannia'' was compelled at last to set up its own printing press. Emmeline Pankhurst proposed to set up Women's Social and Political Union Homes for illegitimate girl "war babies", but only five children were adopted. David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during t ...

, whom Pankhurst had regarded as the most bitter and dangerous enemy of women, was now the one politician in whom she and Emmeline Pankhurst placed confidence.

1918 General Election campaign in Smethwick

After some British women were granted the right to vote at the end of World War I, Pankhurst announced that she would stand in the 1918 general election. At first she said she would contest Westbury in Wiltshire but at the last minute stood as a Women's Party candidate, in the Smethwick constituency in alliance with the Lloyd George/Conservative Coalition. She was not issued with the "Coalition Coupon

The Coalition Coupon was a letter sent to parliamentary candidates at the 1918 United Kingdom general election, endorsing them as official representatives of the Coalition Government. The 1918 election took place in the heady atmosphere of victory ...

" letter signed by both Liberal and Unionist leaders. Her campaign focussed on a "Victorious Peace", "the Germans must pay for the War" and "Britain for the British". She was narrowly defeated, by only 775 votes, by the Labour Party candidate, local trade union leader John Davison.

Move to California

Leaving England in 1921, she moved to the United States where she eventually became an evangelist withPlymouth Brethren

The Plymouth Brethren or Assemblies of Brethren are a low church and non-conformist Christian movement whose history can be traced back to Dublin, Ireland, in the mid to late 1820s, where they originated from Anglicanism. The group emphasizes ...

links and became a prominent member of Second Adventist movement.

Prophetic interests

Marshall, Morgan, and Scott published her works on subjects related to her prophetic outlook, which took its character fromJohn Nelson Darby

John Nelson Darby (18 November 1800 – 29 April 1882) was an Anglo-Irish Bible teacher, one of the influential figures among the original Plymouth Brethren and the founder of the Exclusive Brethren. He is considered to be the father of modern D ...

's perspectives. Pankhurst lectured and wrote books on the Second Coming

The Second Coming (sometimes called the Second Advent or the Parousia) is a Christian (as well as Islamic and Baha'i) belief that Jesus will return again after his ascension to heaven about two thousand years ago. The idea is based on messi ...

. She was a frequent guest on TV shows in the 1950s and had a reputation for being an odd combination of "former suffragist revolutionary, evangelical Christian, and almost stereotypically proper 'English Lady' who always was in demand as a lecturer". While in California, she adopted her daughter Betty, finally having recovered from her mother's death.

Damehood

She returned to Britain for a period in the 1930s and was appointed aDame Commander

Commander ( it, Commendatore; french: Commandeur; german: Komtur; es, Comendador; pt, Comendador), or Knight Commander, is a title of honor prevalent in chivalric orders and fraternal orders.

The title of Commander occurred in the medieval mil ...

of the Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established ...

"for public and social services" in the 1936 New Year Honours

The 1936 New Year Honours were appointments by King George V to various orders and honours to reward and highlight good works by citizens of the United Kingdom and British Empire. They were announced on 31 December 1935.

The recipients of honour ...

.Christabel PanhurstBritannica.com, Retrieved 21 September 2016 At the onset of World War II she again left for the United States, to live in

Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world ...

, California.

Death

Christabel died 13 February 1958, at the age of 77, sitting in a straight-backed chair. Her housekeeper found her body and there was no indication of her cause of death. She was buried in theWoodlawn Memorial Cemetery

Woodlawn Cemetery, Mausoleum & Mortuary, formerly Ballona Cemetery, is located at 1847 14th Street, alongside Pico Boulevard in Santa Monica, California, United States. The cemetery is owned and operated by the city of Santa Monica. The cemetery ...

in Santa Monica

Santa Monica (; Spanish: ''Santa Mónica'') is a city in Los Angeles County, situated along Santa Monica Bay on California's South Coast. Santa Monica's 2020 U.S. Census population was 93,076. Santa Monica is a popular resort town, owing to ...

, California.

Posthumous recognition

A profile bust of Christabel Pankhurst on the right pylon of the

A profile bust of Christabel Pankhurst on the right pylon of the Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst Memorial

The Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst Memorial is a memorial in London to Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughter Christabel Pankhurst, Christabel, two of the foremost British suffragettes. It stands at the entrance to Victoria Tower Gardens, south ...

in Victoria Tower Gardens

Victoria Tower Gardens is a public park along the north bank of the River Thames in London, adjacent to the Victoria Tower, at the south-western corner of the Palace of Westminster. The park, extends southwards from the Palace to Lambeth Bridge, ...

was added to the memorial in 1959; it was unveiled on 13 July 1959 by Viscount Kilmuir

A viscount ( , for male) or viscountess (, for female) is a title used in certain European countries for a noble of varying status.

In many countries a viscount, and its historical equivalents, was a non-hereditary, administrative or judicial ...

. Her name and image (and those of 58 other women's suffrage supporters) are etched on the plinth

A pedestal (from French ''piédestal'', Italian ''piedistallo'' 'foot of a stall') or plinth is a support at the bottom of a statue, vase, column, or certain altars. Smaller pedestals, especially if round in shape, may be called socles. In c ...

of the statue of Millicent Fawcett

The statue of Millicent Fawcett in Parliament Square, London, honours the British suffragist leader and social campaigner Dame Millicent Fawcett. It was made in 2018 by Gillian Wearing. Following a campaign and petition by the activist Caroline C ...

in Parliament Square

Parliament Square is a square at the northwest end of the Palace of Westminster in the City of Westminster in central London. Laid out in the 19th century, it features a large open green area in the centre with trees to its west, and it contai ...

, London, that was unveiled in 2018.

In 2006, a blue plaque

A blue plaque is a permanent sign installed in a public place in the United Kingdom and elsewhere to commemorate a link between that location and a famous person, event, or former building on the site, serving as a historical marker. The term i ...

for Christabel and her mother was placed by English Heritage

English Heritage (officially the English Heritage Trust) is a charity that manages over 400 historic monuments, buildings and places. These include prehistoric sites, medieval castles, Roman forts and country houses.

The charity states that i ...

at 50, Clarendon Road, Notting Hill

Notting Hill is a district of West London, England, in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Notting Hill is known for being a cosmopolitan and multicultural neighbourhood, hosting the annual Notting Hill Carnival and Portobello Road M ...

, London W11 3AD, where they had lived. Another blue plaque was erected on 19 October 2018 by the Marchmont Association at 8, Russell Square

Russell Square is a large garden square in Bloomsbury, in the London Borough of Camden, built predominantly by the firm of James Burton. It is near the University of London's main buildings and the British Museum. Almost exactly square, to the ...

, London WC1B 5BE.

Works

*See also

*History of feminism

The history of feminism comprises the narratives (chronological or thematic) of the movements and ideologies which have aimed at equal rights for women. While feminists around the world have differed in causes, goals, and intentions depending ...

*List of suffragists and suffragettes

This list of suffragists and suffragettes includes noted individuals active in the worldwide women's suffrage movement who have campaigned or strongly advocated for women's suffrage, the organisations which they formed or joined, and the public ...

*Suffragette bombing and arson campaign

Suffragettes in Great Britain and Ireland orchestrated a bombing and arson campaign between the years 1912 and 1914. The campaign was instigated by the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), and was a part of their wider campaign for women's ...

*List of women's rights activists

This article is a list of notable women's rights activists, arranged alphabetically by modern country names and by the names of the persons listed.

Afghanistan

* Amina Azimi – disabled women's rights advocate

* Hasina Jalal – women's empowerm ...

* Pankhurst Centre in Manchester

*Timeline of women's suffrage

Women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant ...

*Women's suffrage in the United Kingdom

A movement to fight for women's right to vote in the United Kingdom finally succeeded through acts of Parliament in 1918 and 1928. It became a national movement in the Victorian era. Women were not explicitly banned from voting in Great Britai ...

* Women's suffrage organisations

References

Further reading

* Christabel Pankhurst, ''Pressing Problems of the Closing Age'' (Morgan & Scott Ltd., 1924). * Christabel Pankhurst, ''The World's Unrest: Visions of the Dawn'' (Morgan & Scott Ltd., 1926). * David Mitchell, ''Queen Christabel'' (MacDonald and Jane's Publisher Ltd., 1977) *Barbara Castle

Barbara Anne Castle, Baroness Castle of Blackburn, (''née'' Betts; 6 October 1910 – 3 May 2002), was a British Labour Party politician who was a Member of Parliament from 1945 to 1979, making her one of the longest-serving female MPs in Bri ...

, ''Sylvia and Christabel Pankhurst'' (Penguin Books, 1987) .

* Timothy Larsen, ''Christabel Pankhurst: Fundamentalism and Feminism in Coalition'' (Boydell Press, 2002).

* Hallam, David J.A.br>Taking on the Men: the first women parliamentary candidates 1918(Brewin Books, 2018 . Contains a chapter and analysis on Christabel Pankhurst's campaign in Smethwick, 1918.

External links

*1908 audio recording of Christabel Pankhurst speaking

* http://www.spartacus-educational.com/WpankhurstC.htm

Blue Plaque for Suffragette Leaders Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Pankhurst, Christabel British feminists English feminists English suffragettes English women writers Feminism and history Alumni of the University of Manchester Dames Commander of the Order of the British Empire People from Los Angeles People from Old Trafford 1880 births 1958 deaths People educated at Manchester High School for Girls Burials at Woodlawn Memorial Cemetery, Santa Monica Christabel Eagle House suffragettes Women's Social and Political Union